A unified theory of media greatness

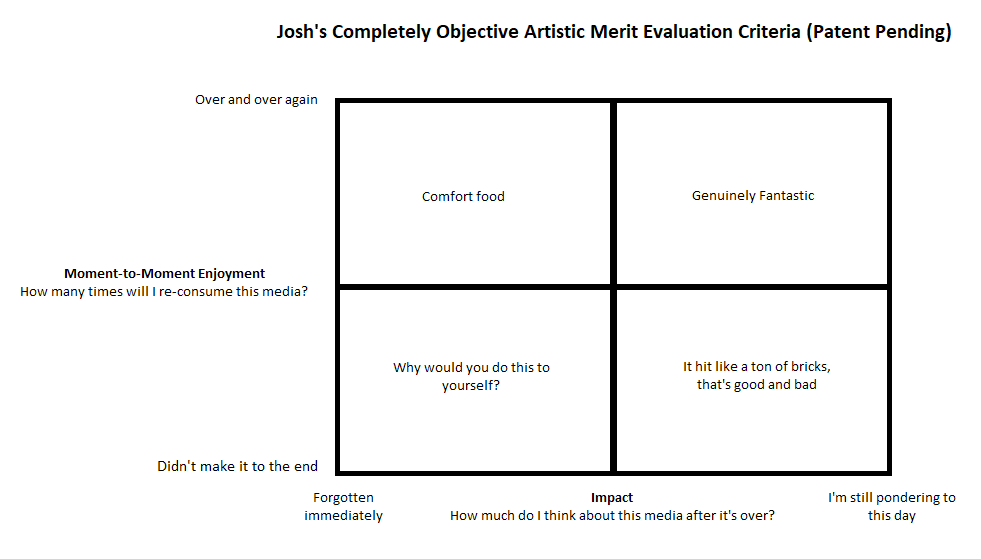

Before we get into Liu Cixin’s books, let’s outline what I think makes a book/movie/album/whatever great. And I’m going to do it using the tried-and-true, creative-friendly, FOUR BOX MODEL. Just like they teach in film school:

I’m sure film school has some actual criteria, but as I thought about movies I watch I realized this is a good way to compare. On the Y axis we have “Moment-to-moment enjoyment” — basically, how fun or fulfilling is the act of actually consuming your media of choice?

The best way to figure this out is to ask yourself how many times you re-consume it. Generally if you enjoy the actual experience of reading a book, you’ll read it more than once. What makes you enjoy it? Well that varies from person to person, and even from book to book. Here’s a few examples for me:

- Dune — they’re just very compelling to read, it’s easy to get lost in the world of Arrakis

- Raymond Chandler books (and to a lesser extent Dashiell Hammett) — the writing is always fantastic and propulsive, evocative, but in such a creative way

- The Hitchhiker’s Guide series — These are hilarious and every time I read them I find myself laughing aloud every chapter

Next is impact — this is a way of measuring the ideas of a book or movie. Does it get me thinking? A few days after reading or watching something, ask yourself if it’s still on your mind.

Again, this is highly personal. A few example of things that were very impactful for me:

- The Toyota Way and Toyota Kata — fantastic books that changed how I think about my work

- Spotlight — just sat in silence as the credits rolled and still think everyone should watch it

- Everything Everywhere All at Once — Another film that my wife and I talked about for days after

- Parent Effectiveness Training — best parenting book that exists

- Catch 22 — so funny and so dark that it can’t help but stick with you

You can see that I’ve given each quadrant a brief description as well. Again, this completely objective artistic merit evaluation is, well … subjective. It will be different for everyone, which makes sense. A few examples of things in the various quadrants for me:

- Why?

- Your Next Five Moves

- Master of Disguise

- Comfort Food

- Arrested Development (TV series)

- Raymond Chandler books

- Fantastic

- Bladerunner 2049

- Dune (book, although the 2021 film is also very good)

- Ton of Bricks

- Spotlight

- The Green Mile (the book, although the movie is fine too)

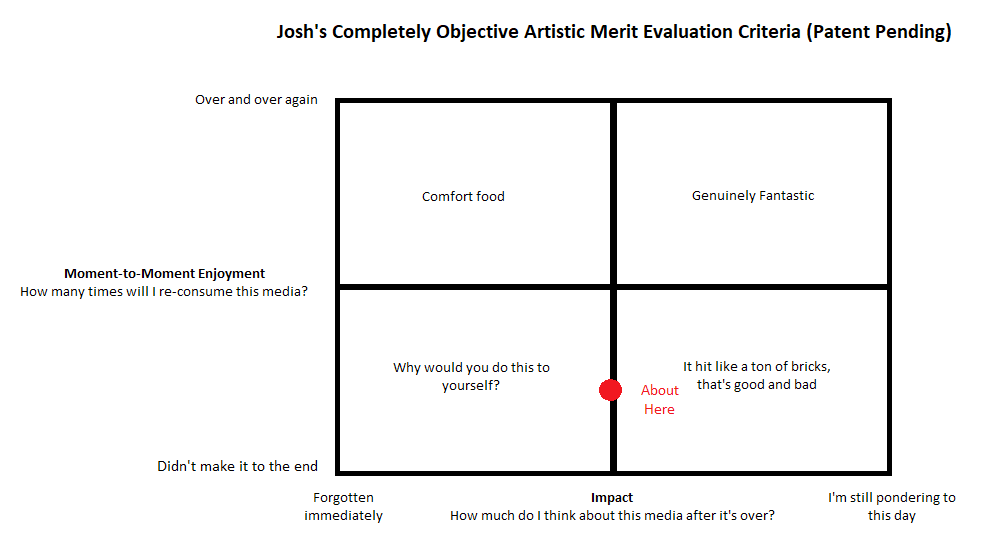

So where does Three Body Problem land on this four-box-model?

Why?

There are a lot of things I didn’t like very much, and a couple of things I did like. Let’s start with the complaints, and end with the praise.

Complaint 1: The Writing Falls into “Golden Age Science Fiction” traps

In the US, “Golden Age Science Fiction” is generally considered 1940(ish) to 1960(ish). My main problem with Golden Age Sci-Fi is that it was big on ideas, short on quality writing. Typically you would have cardboard cutout characters get together and then discuss a technological, philosophical, or techno-philosophical problem. Isaac Asimov is an example of this. His books are full of creative, prescient ideas and flat characters who discuss these ideas. You read Asimov for the concepts, not the prose.

The main problem with writing of this era is it ignores “Show, don’t tell.” Instead of a character behaving in a way that reveals what they think, feel, or are capable of, it just straight up says it. Instead of showing how a technological solution might be problematic, they again just have a character point out that something is problematic.

Liu falls into this same trap — interesting ideas, but the writing doesn’t stand out. I can’t really blame this on translation as the problem isn’t necessarily the word choice, it’s more the characterization. It could also be cultural, though. It’s possible actions taken by characters were showing and not telling, but the implication went over my head because I’m not familiar with Chinese Culture. Someone who is more familiar with the culture, please correct me if that’s the case.

This moves the book down the left axis in our model.

Complaint 2: The plot tends to meander and drop threads

This is especially true in the second book. Let’s look at one example (major spoilers coming up!)

Without getting too into the details, earth decides to give four people basically unlimited resources in order to create strategies to fight an alien invasion that’s coming in 400 years. These people are called “Wallfacers.”

One wallfacer is a neurologist and doesn’t know what to do, so he decides to just do some advance research he wouldn’t normally have the funding to do. He hibernates for some years so technology can catch up to his plans, then discovers that the research he put in motion has created mind control — it’s possible to indoctrinate people to believe a specific statement is true (or false) by blasting their heads with microwaves while they contemplate the statement in question (basically).

Obviously people are upset about this (an interesting conversation ensues) so they compromise and create a single, tightly controlled location where people can be indoctrinated with just one statement (that humanity can win the war). This is used to help soldiers avoid despair.

EXCEPT they secretly built FIVE mind-control devices (twist number one) and later you find out (continuation of twist number one) that people may have used those devices to secretly indoctrinate TONS of other people (though maybe not). Which may or may not be a good thing.

EXCEPT the wallfacer secretly programed the mind-control devices to convince people they COULDN’T win the war (twist number two). So maybe there’s a huge, secret society of people convinced that they can’t win and they should instead attempt to escape the galaxy. Or maybe there’s a small secret society. Or no secret society. Or just one dude but it’s no longer a secret.

We don’t ever find out. Although Liu uses this whole plot as justification to allow another character to gain control of a starship it just is so … weird. Why introduce all this when you could’ve made two pages of justification for the other character and call it good? Why talk about it at all? It doesn’t add anything to the plot, it doesn’t move things forward. It just kind of moves things … around.

Again, it’s that golden age sci-fi trap. An interesting idea, but it’s just kind of crowbarred into the plot so the author can use his characters to discuss the philosophy of it. If you enjoy that type of discussion then this would probably move the book up the left axis for you, but for me it was definitely a negative.

Complaint 3: Oh man, the ethnocentrism

Honestly, I think most people liked this book a lot more than me, and this is the reason for it. Many people are happy with the idea of other alien races that behave more or less like our own — that are just as violent, selfish and short sighted as we are.

But I’ve just gotten tired of this idea. And the idea that species that can travel through interstellar space would bother hunting down other species and starting wars just … doesn’t make sense to me.

Imagine, for a second, that we’re back in neanderthal times. The world is huge. There are resources everywhere. There are very, very few people.

In fact, let’s imagine that there are just two groups of people — two small villages with less than 1000 people. One is located where modern day Hong Kong will one day be, the other is located in Argentina. These two places are on completely opposite sides of the globe from each other. To travel from one to the other would be a voyage of years.

Now let’s imagine that one person in one of these village calls a meeting and says “Listen guys, first off, the earth is a big ball. I know this is big news, but I’m not done dropping truth bombs. Second off, on the exact opposite side of this ball there is a group of people the same size as us. They’re just over there, eating some kind of plants and animals that maybe we don’t have here, living their lives, making babies and singing some kind of Argentinian songs or whatever. I think we should go murder those guys.”

“But why?” asks literally everyone in the village who doesn’t want to travel what could be like … a quarter of their entire lifespan just for genocide.

“Because one day they may pose a threat to us. The earth is big, but there are limited resources. I think several millions, maybe tens of millions, maybe hundreds of millions of years in the future our descendants could be fighting their descendants for food or water or even our own dead bodies that have turned into petroleum over the eons. Let’s not let it come to that. I say we murder them now. To the boats!”

That’s crazy to think about, and here we’re talking about one planet. Now imagine infinite planets orbiting infinite stars. Why would the Trisolarians (the aliens from the book) come to our star system? I mean, we’ve determined that they can hibernate and travel between stars, why not just go … literally anywhere else in the entire universe?

The second book attempts to answer that question by saying that all civilizations invariably get to the point where they think the best course of action is to murder everyone in the entire universe that isn’t them. They do this because there are limited resources, and because, due to the nature of technological leaps, if they don’t kill other civilizations, those civilizations will just leap-frog them and then kill them.

What’s funny to me is that I had a complaint about the first book, and then the second book is basically Liu EXTREMELY doubling down on my complaint from the first book. There’s no other theories. There’s no voice saying “maybe everyone doesn’t want to murder everyone.” The end of the second book is just everyone nodding their heads going “Man, isn’t it crazy how everyone wants to murder literally everyone else all the time and there is no hope and no civilization could ever come to a different conclusion!?!”

Again, I think this could be a cultural difference, but I think it’s an important one to discuss.

Chinese politics are socialist, and Mao Zedong was heavily influenced by Marx. Marxism is all about conflict over scarce resources. This is a gross simplification, and I may misunderstand how influential Marxist thought is in China, but the idea that all species would compete over basically unlimited resources to the extent that they preemptively destroy each other feels very Marxist to me — it feels like someone taking that school of thought to the logical, universal conclusion.

And I guess that’s my fundamental disagreement. It’s not about the politics or policy, it’s about the philosophy of the scarcity of resources itself. Although we don’t know if the universe is infinite, functionally I think we can say it is. Look at the first Deep Field image from the James Webb Telescope. Hundreds of galaxies are plainly visible in this one image, each with hundreds of billions of stars. And this one image is roughly the size of a grain of sand held at arms length.

Why would civilizations worry about each other? Why would they fight over resources? Why would they go out of their way to destroy each other? It makes as much sense as a neanderthal travelling around the world to bash another neanderthal in the head with a rock.

It bothers me that no one in the book proposes any other solution. No one says “Maybe there are other species that can help us.” The only thing other civilizations are good for in these books is to use to destroy (or threaten to destroy) the only other civilization that earth has ever successfully communicated with. How bleak!

And yet, that seems to be the standard story. Humanity encounters another species, and immediately gets in a fight with them. I miss optimistic science fiction. Something like Star Trek the Next Generation, where the conflict in most episodes is simply due to difficulties interacting with other species, and once an understanding is reached the conflict can be avoided, or at the very least understood.

What did I like about it?

Some of the concepts and ideas were interesting. The sophon was interesting, the mathematical heart of the three body problem was interesting as well. The idea of another culture using a video game to help us understand them was really interesting.

What surprised me most was how interested I was in just .. actual Chinese history. Reading about the cultural revolution was shocking, and it made me want to learn more. To understand where this country comes from, and how they became who they are.

Several of the footnotes would say things like “So and so was like the Chinese Marie Curie” or “so and so won a nobel prize in physics” and I was embarrassed to be so ignorant of Chinese history given their importance in the world (and to the United States in particular). So really, I liked that it just whet my appetite to learn more about another culture.

If anyone from China, or familiar with their history, is reading this, please recommend some good Chinese History books for me!

I also liked the Da Shi a lot. Best character in the books!

2 responses to “Review: The Three Body Problem (and the Dark Forest)”

[…] are other possible explanations as well. You may remember from my review of the Three Body Problem (and the Dark Forest) that Liu […]

LikeLike

[…] mean, but I don’t think it’s actually that mean. For one thing, he’s part of a proud tradition of science fiction writers who have a hard time writing believable, unique people. In science […]

LikeLike