In our last (rather long) blog post we talked about how to turn a WHY into ACTION. It centered around this six(ish) step process:

- Figure out WHY you’re doing something (we did this!)

- Figure out a challenge or Target Condition

- Grasping the Current Condition (or figuring out “What’s Going On Here”)

- Finding gaps between current condition and target condition

- Creating metrics to measure your progress

- Experimenting your way to your target condition

- Now rinse and repeat!

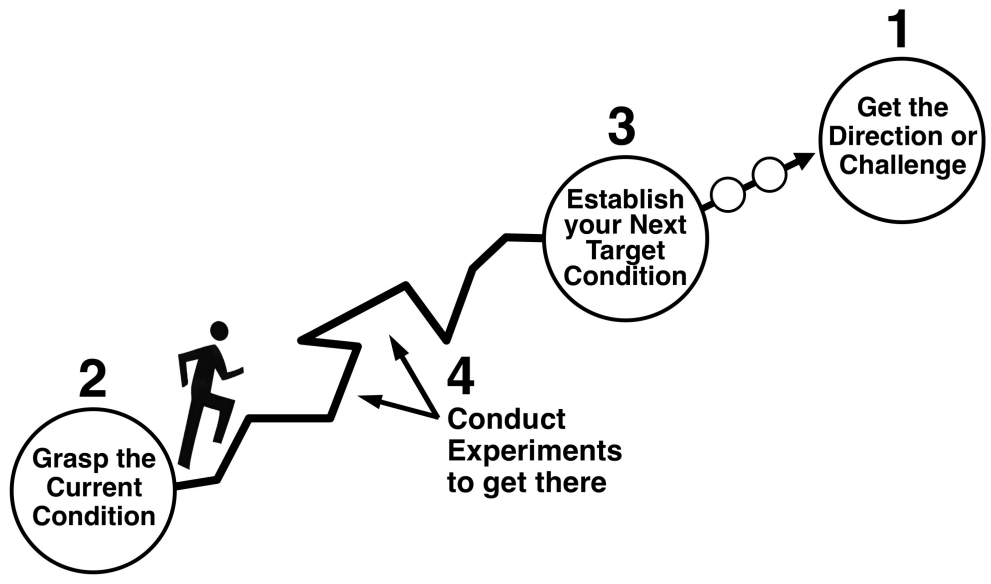

We touched on “experimenting your way to your target condition” which is mentioned in this helpful chart from Toyota Kata:

The section about conducting experiments is kind of the meat of the Toyota Kata system, but it can be summarized in a really simple, widely known pattern:

- Plan

- Do

- Check

- Act

AKA PDCA.

By performing PDCA cycles, you gradually bring yourself closer to your next target condition. So let’s talk (briefly) about PDCA, and then discuss the thing I wanted to focus on.

What is PDCA?

PDCA has four steps. To give a little more detail:

- PLAN what you’re going to do. This means creating a specific, time-boxed, measurable, single variable change. You should plan exactly what you’ll do AND predict what effect you expect it to have (and what you don’t expect to change).

- DO your plan! Make sure you do it exactly as planned, for long enough to get good data (more on that in a second)

- CHECK the effect your plan had. Did it behave as you predicted? Were there unintended consequences?

- ACT — if the experiment went well, you make it a new standard! If it didn’t, you throw it in the garbage, where it belongs!

Toyota Kata, and performing PDCA cycles, is actually a whole discipline that requires a lot of practice. But I want to answer one really common question: when you start an experiment, how long does it take to know if it’s successful?

Let’s look at two examples. The first one start with my time as a missionary.

Can you teach better?

I served a mission for the LDS church in Brasil, a country and people that I really came to love. I don’t know if you’re familiar with what missionaries do on a day-to-day basis, but it’s pretty simple:

- Wake up and study the scriptures for a couple of hours

- Go out and try and find people who want to hear our message, usually with one of these methods:

- Visiting members of the church to see if they knew anyone who wanted to hear it

- Talking to people on the street

- Going door-to-door

- Teach some people

- Go home and sleep

You did all of this with a “companion” — someone you were with 24 hours a day for at least six weeks (every six weeks there was an option to move people around).

In the beginning you might have very different contacting or teaching styles, so I after every message (and even some contacts) we would stop and I would ask “How do you think that went?” and we’d discuss what went well and what we could potentially do better.

One message was enough to find out that you were talking over each other, and so one message was enough of a feedback loop to make meaningful changes.

(that compulsion has stuck with me — I usually ask for feedback after every board meeting, every conference talk, even just plain ol’ meetings sometimes).

How do you improve a website?

For a while I managed a development team that built the website for a theater chain. One of the issues we got complaints about was our checkout process — it was multiple pages and led to a decent amount of confusion.

Before we could start fixing it, though, we had to figure out what was going on. We added software that would track users as they go through the checkout process, and tell us where they dropped out.

What we found out was … they dropped out all over. There were tons of problems. So we did a bunch of research and redesigned the checkout process so it all happened on one page. This led to a pretty big reduction in abandoned carts, but we kept watching. We noticed a specific button might trip some people up. Or maybe they were confused about when they should log in. We would make a change, then wait to see what kind of effect it had.

The problem with a theater is that the product (the movies) is outside of our control. So it wasn’t enough to make a change and watch it for one day and decide if we wanted to keep it or not. We might have a spike in traffic because a new Avengers movie came out and attribute that to our amazing changes, even though that had nothing to do with it at all.

In the end we decided to not perform these experiments around big openings (too risky anyway), and instead to watch changes for roughly a week. A sample of different days allowed us to see if the changes in behavior were due to our work, or just random chance.

So how long should an experiment be?

Exactly long enough to receive meaningful feedback, which will be different for most situations. How often do you collect feedback? No, seriously. Think about your job. Ignore what you’ve set up for reporting and ask yourself “How often am I collecting meaningful feedback?” How much reporting is just because you think you should be watching it? How much is actually leading to changes?

That’s kind of the key — how often do you receive information that prompts you to change something in a structured way? Take a minute and write down your five most recent feedback experiences.

Were they today? Were they this week? Were they this month?

Who did you seek feedback from? Your boss? Your customer? Your team? Your colleague? Your significant other?

The point is, you should be learning and improving every day, and it’s difficult to learn and improve without feedback. This is double true if you find yourself in a new situation.

You may encounter some people who don’t like that. I’ve had more than one manager who said “Hey, don’t ask me for feedback, no news is good news.”

Ask anyway! If they’re your manager, they need to be invested in your improvement. And if they still refuse, find people who are invested in it. Ask over and over again. Ask everyone. That’s how you get better.

UPDATE

After I posted this my wife read it and sent me a quote from it, making a joke. After chatting about it for a minute I asked her, “Any other feedback?”

She did agree that this was an important part of my personality, and probably a contributor to whatever success I’ve had. Thanks for the feedback!