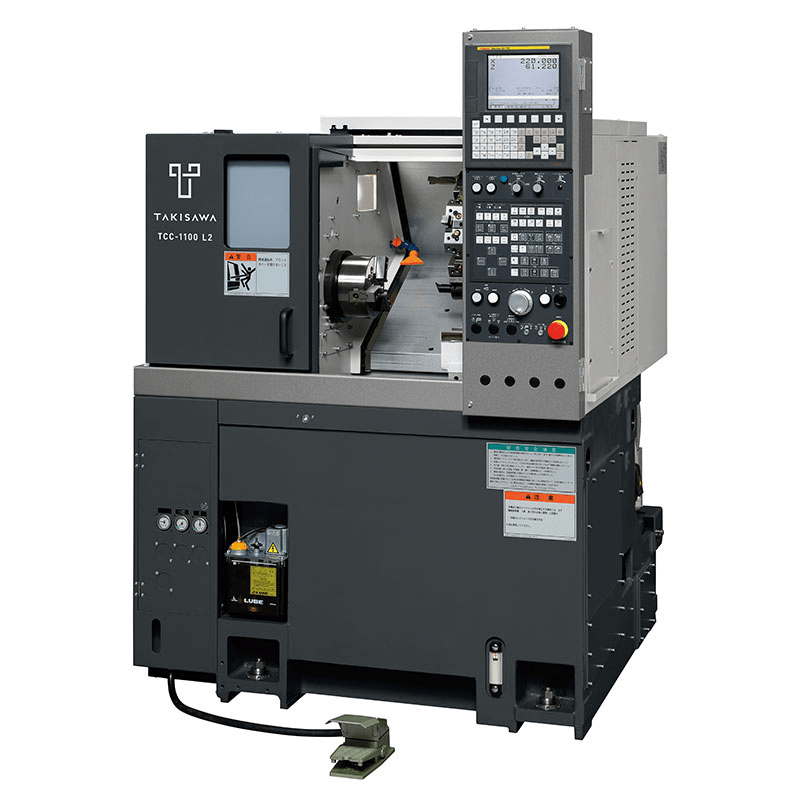

Just after high school a friend of mine started working at a CNC machine shop. He was running a part on a lathe that looked a lot like this (though this is a much newer model):

You can see on the left there’s a sliding door that’s open in the picture. Inside the machine is the “collet” that holds the raw material in place, and to the right is the control panel (with the big red emergency stop button).

When working this machine you’d generally follow these steps:

- Put your raw material in the collet, then press the button (or foot switch) to close it

- Slide the door closed

- Press the “Start” button

- Wait for the job to finish

- When it’s completely done (you could usually tell because the coolant turned off) open the door

- Grab the finished piece and remove it

- Put a new piece of raw material

- Repeat for eight to ten hours

(I also worked in a machine shop after high school, though not the same one, so my memories of this process are pretty vivid)

The machine my friend was using had one unfortunate issue. The safety shutoff on the door, that kept the machine from running when the door was open, was disabled. My friend placed the raw material in the collet, then held it there with his palm while he reached over to press a button to close the collet. Except instead of pressing the “close collet” button, he pressed the “start” button. The machine whirred to life and, before my friend had a chance to blink (let alone hit the emergency shutoff), a tool came down and punched directly through his palm, boring out the inside of the piece he was holding, along with his hand.

Miraculously, my friend was okay. I mean, it was disgusting, and it took quite a while to heal, and he still has a scar, but the tool missed his major tendons and muscles and his hand would regain normal motion. Eventually.

There’s a saying: safety regulations are written in blood. Somewhere, that chain of events had already happened to someone, and some government body had made a regulation that CNC lathes of that type should have a shutoff connected to the door. When the company my friend worked for disabled the shutoff (probably with harmless intention — to do it temporarily while they did some manual buffing on some parts at a slower speed, or because the door alarm kept going off when it shouldn’t) they ignored the blood that had already been spilled, and learned the purpose for the regulation all over again by spilling more blood.

The two reasons for documentation

There are two reasons people write documentation:

- For compliance purposes (IE they need to check a box)

- To improve the security posture of their organization

You can do both at once. In fact, improving the security posture of the organization almost always helps with compliance. But it is possible to write a policy, and stick that policy in a binder, and only look at it once a year when an auditor comes around.

So the first step to writing good policy (and good documentation in general) is to do it to genuinely improve your security posture, and not just to be a box checker.

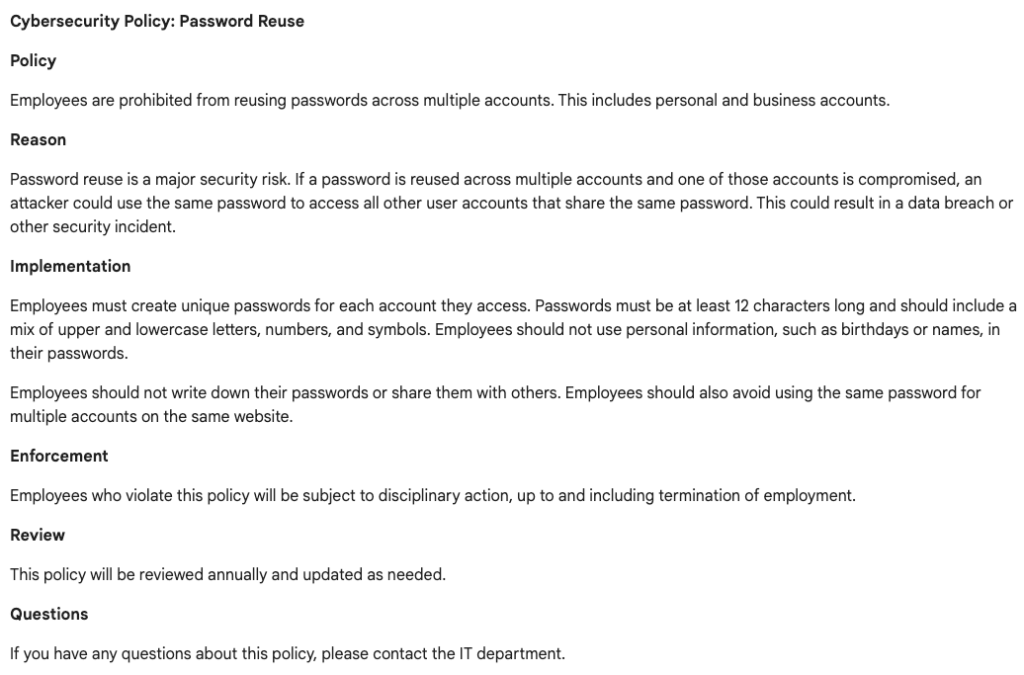

If you want to be a box checker I can’t stop you, obviously. You are completely free to go to ChatGPT (or Google Bard) and ask it to “Write a password reuse policy” and it will spit out something about on par with what a beginner cyber security student could produce in twenty minutes of work:

But if you do that you’re missing the point. Somewhere, someone paid in time, money or their job because they didn’t have a good policy in place. If you treat writing documentation as a “box checking” exercise then you’re ignoring the lessons available to you, and instead insisting that you learn it for yourself at some future point. So that’s the first key to writing good documentation:

Take writing documentation seriously

What I mean is, as you read through regulatory or government requirements, take the time to understand what they are actually for. Let’s use an example of PCI DSS 4.0, requirement 8.2.2 (literally chosen completely at random). It reads:

Group, shared, or generic accounts, or other shared authentication credentials are only used when necessary on an exception basis, and are managed as follows:

- Account use is prevented unless needed for an exceptional circumstance.

- Use is limited to the time needed for the exceptional circumstance.

- Business justification for use is documented.

- Use is explicitly approved by management.

- Individual user identity is confirmed before access to an account is granted.

- Every action taken is attributable to an individual user.

PCI version 4.0 actually includes the purpose behind every requirement right there, under a section called “Customized Approach Objective” (in case you can’t comply with the requirement as written, but still want to comply with the overall purpose). The customized approach objective for 8.2.2 reads:

All actions performed by users with generic, system, or shared IDs are attributable to an individual person.

It’s easy to see why this might have happened. Imagine a retail store with lots of tills. Typically to unlock a till you have to input a PIN, but imagine if everyone just used the same PIN. At the end of the night the till is short $50. Who took the money?

If you don’t have the ability to attribute actions to an individual it could be really hard to figure out — especially if dozens of employees have come through that day. It could take weeks, or months, to find out the real culprit, and all that time you’d be losing a little money every day. Maybe a lot of money. I know of some fraud cases very similar to our example that totaled in the tens of thousands of dollars before the culprit was finally identified.

Write the right thing

Second, and we’ll get to the why in a second, but your documentation needs to be clear and easy to understand. That also means that you need to write the right things, and name the things that you write the right things so that when they read the things you wrote rightly they’ll … ok, hang on, let me just … define some stuff.

| Term | Definition | Example |

| Policy | Technology or implementation agnostic declaration of a desired outcome | All passwords shall be secure according to industry standards |

| Standard | A uniform technology or other tool used to implement a policy | We use Google Workplace for our account management |

| Guideline | Advice around how to achieve a policy | A “Secure Password” is one with at least 12 characters, numbers and letters, can’t be the same as last four passwords, etc. |

| Procedure | A step by step guide to accomplishing the policy outcomes using the standard technology and advice in guidelines | 1. Go to google password settings manager page 2. Set minimum character length to 12 3. Set complexity requirements to “medium” etc. |

There is some crossover between these documents, and some sources will define them differently, but this gives you the basic idea. Typically, one thing leads to another. So a business may need to comply with a regulation (like PCI DSS, HIPAA, or a specific security framework). They’ll use that regulation to write policies. They’ll use the policies to decide on the best technology to achieve the outcomes and standardize on those, produce guidelines as necessary, and then write procedure documents to implement the technology to fulfill the policy to, ultimately, comply with the regulation or framework.

So understanding the “why” behind the regulation or framework makes writing the policy more effective, and everything down the chain from that relies on effective policy. So how you write your policy is really important, which brings us to our next point.

Don’t write like a lawyer

Some of my best friends are lawyers! And they would agree that legal documents typically aren’t written to be easily readable. They’re written to hold up in court, to require lawyers to decode them (thus insuring their continued employment), and occasionally to make other lawyers laugh with esoteric, well hidden references and in-jokes about … the bar? I don’t know, IANAL.

Most policy and procedure documents you read are long and complicated, and do tend to sound pretty lawyerly. An example from the SANS institutes template for an Acceptable Use Policy:

<Company Name> proprietary information stored on electronic and computing devices whether owned or leased by <Company name>, the employee or a third party, remains the sole property of <company name>. You must ensure through legal or technical means that proprietary information is protected in accordance with the Data Protection Standard

The policy goes on using similar verbiage for six pages — just for an acceptable use policy!

Is that anymore clear than just writing:

Company data always remains the property of the company, and each employee is required to protect company data according to the Data Protection Standard, regardless of the device used to access it.

The second example contains the same information, but it is much easier to understand and, as a bonus, just over half as long.

Listen, I’m a guy that writes blog posts about cybersecurity for fun, so maybe I romanticize the power of the written word a little, but even boring documentation can be written well. It doesn’t have to be Hemginway or Falkner. It doesn’t even have to be Stephanie Meyer. But it can be clear and concise. Most importantly, if it is clear and concise it stands a much better chance of hitting our final requirement for documentation that doesn’t suck:

It has to work in real life

A few years back we got a template for an incident response plan from a consultant. This plan was thorough. It was comprehensive. It was also lawyerly. It was 16 pages long. It was single spaced. It was 12 point font.

If you’re unfamiliar with an incident response plan, it’s the document you use when there’s been a major incident that you need to respond to, such as a ransomware attack.

In any kind of incident, even just a regular outage that isn’t a cyber attack, time is of the essence, and the first people responding to an incident are generally helpdesk agents. Picture, if you will, a helpdesk agent determining that an incident is “Priority 1” and needs to be responded to. Imagine them pulling up the Incident Response plan and reading the first page — the scope of the incident response plan. Roles and responsibilities. Containment procedures. Legal implications. How long does it take to find out the person to call? I mean, how long just to find the bullet point on page seven that says they need to call someone? And then how long to flip to the appendix at the back of the plan that has contact info?

Obviously this wouldn’t work, and tabletop exercises proved it. We would sit around a table, simulate an event, and then the helpdesk would completely ignore the incident response plan and just do whatever they felt was the best option. And who can blame them?

I’ve seen lots of ways of improving the incident response plan. Right now we have a three page incident response plan we use for training, along with a one page cheat sheet that the helpdesk can refer to in the event of an actual incident (and that can be printed up and posted by their desks). Tabletops with this version of the incident response plan tend to go much better.

Another place I worked went one step further. They knew that most incidents happened after hours, when the helpdesk would be away from their desk, so they made business cards with a brief summary of the IRP on one side, and contact info for escalation points on the other. It was fantastically usable in real life.

It’s not enough that a policy is written well — it has to work, in real life. That means, after writing your policy, and after disseminating it and training everyone, you have to actually go around and see how it’s being followed. Do people need resources to follow it? Additional training? Other tools? Does the policy itself need to change? Or maybe the standard, guidelines or procedure?

The point is, don’t treat any document as a finished product. All of them can be improved, and the only way you’ll know how to improve them is to see how they’re used in real life, and sometimes to test how they might be used in an emergency. Then go back and make it better. Then do it again, over and over until you’ve created the perfect, gleaming, wonderful document. That you will still need to update when something new comes up.

So let’s summarize

Writing documentation is important, and good documentation can materially improve your security posture! But it has to be GOOD documentation, and that means:

- Take writing documentation seriously

- Understand the why behind the regulation, law or framework

- Write the right thing

- Policy — the desired outcome

- Standards — the technology you’ll use to get it

- Guidelines — advice on how most people achieve that outcome

- Procedures — a step by step guide to implement the standard in order to achieve the policy outcome

- Don’t write like a lawyer

- Clear and concise > long and lawyerly

- It has to work in real life

- See how your document is implemented in practice, then improve it

If you do those things, you’ll make good policy that will make your organization more secure. Or, you know, you could be a box-checker, and leave the policy writing up to the same AI that made this poem: